There is never one ‘better’ time of year than another to be a teat, though one would like to think of summer as a good season to air those orifices. However recently we have seen a spate of teat calamities and as usual the cows weren’t giving us any clues as to how they happened!

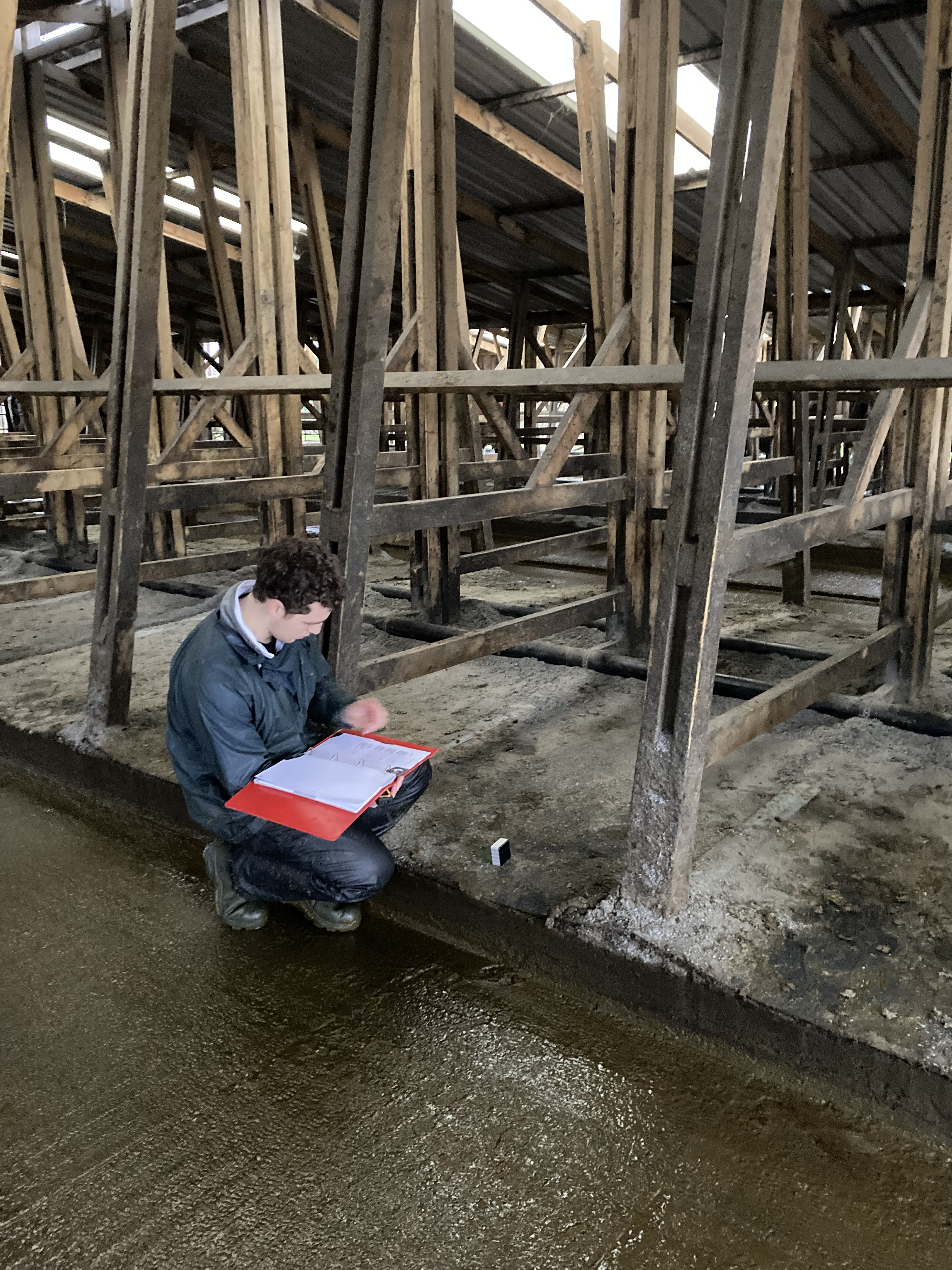

Good restraint is particularly important for safety and to enable the meticulous nature of teat surgery. Many teat repairs are aided by lifting a leg in a crush or putting the cow in the parlour with a kick bar on.

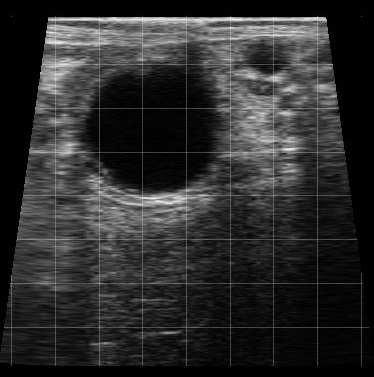

There are two types of traumatic injury-those with perforated teat canals and those with intact teat canals. The direction of the damage is also important-either vertical and/or horizontal. If milk is produced from the cut then the teat canal has been perforated, these are emergencies and should be treated as soon as possible in order to try save the function of the teat. If they are left to heal by themselves, a semipermanent hole (known as a ‘fistula’) may occur. Sometimes we dry these quarters off if the lesion is not fresh ( > 12 hours old) or grossly contaminated and attempt surgical repair at a later date (e.g. at whole udder drying off), working in good operating facilities, with adequate light, cleanliness and efficient analgesia.

Blood vessels through the teat travel vertically so any horizontal cut will compromise supply to the teat below it and can cause the tissue to die. In general, the sooner (<12hrs) a teat injury is tended to the better the potential outcome.

Teats have five specialised layers, though for the purposes of surgery layers 2,3 and 4 are considered as one. This makes repairing them very fiddly! Depending on the nature of the injury teats may be sutured, stapled, glued or a combination. Bandages or honey may also be applied to assist with the healing. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAID) are recommended to reduce pain and inflammation. Intramammary antibiotics may be indicated to reduce the change of mastitis. As milking may be very painful, teat cannulas may be inserted into the teat canal to help let milk out without stripping or milking. Teat tissue heals quickly, similar to our mouths and most sutures/staples can be removed after 10-14days

Factors affecting the outcome and prognosis include: –

- Involvement of the streak canal worsens the prognosis for return to a normal milk flow

- Direction of wound: longitudinal wounds heal better than transverse ones

- Integrity of the blood supply to the lower wound margin may be minimal in the case of a horizontal wound

- Degree of wound contamination and the presence of infection

- Amount of skin loss

- Always consider a conservative treatment by drying off the quarter; surgery is not always the best option

Dedicated after-care by the stockman and veterinarian is of major importance for success. Apart from wound breakdown and local infection, mastitis remains the major hazard. Teat injuries significantly increased test day SCC by 128,000 cells/ml of milk and up to 40% of teat traumatised cows are culled for mastitis within, or at the end of, that particular lactation.

Possible causes of wound breakdown:

- Severe post-operative oedema

- Infection

- Necrosis of wound edges

- Leakage of milk through the mucosa layer

In addition to vet costs, there are losses due to reduced milk yield, discarded milk and possible loss of quarter if there is a necessity to dry it off.

No matter how small, teat injuries are significant and are best treated promptly to minimise potential losses. Please speak to your vet about zero milk withdrawal NSAID’s which can be an option when dealing with injuries such as these.

Leave A Comment