Rob Hall continues his look into infectious diseases with BVD and Fluke up this month…

BVD

Bovine Viral Diarrhoea Virus (BVD) is very common in UK cattle, with surveys showing it is present on approximately 95% of farms and that roughly 65% of adult cattle have encountered the virus and have detectable antibodies.

Infection is transmitted mostly via faeces but also in secretions from the nose and eyes as well as in the semen of infected bulls. Animals that become infected generally shed the virus for a short period of time before they make antibodies to it and recover. The main spreaders, however, are animals that are infected before they are born (as a foetus in the womb), which go on to become persistently infected animals (PIs). These animals shed the virus continually for the whole of their lives and spread the infection to all animals they come into contact with.

In non-pregnant adult cattle infection usually results in a high temperature and milk drop – a scour may also be present, hence the name Bovine Viral Diarrhoea. Cows usually recover spontaneously with no treatment.

However, the virus is immuno-suppressive and so other infections at the same time are more likely and can be more severe. This is particularly important in young stock and it is common for BVD to be associated with pneumonia.

When BVD affects pregnant animals it can cause embryo loss or later abortion. Developmental abnormalities can also occur e.g. calves born with cataracts or with deficits in balance and motor control (shaky calves). If unborn calves become infected during the first 120 days in calf, apparently normal but persistently infected (PI) calves can be born. Some of these animals die of “mucosal disease” in the first two years of life but some survive for many years and themselves have PI calves.

Bulk milk antibody testing as part of the Infectious Disease Check allows us to identify any exposure of the milking herd to BVD.

Strong>Sudden Increase in antibody level – introduction of PI in herd

High and stable – response to vaccination or PI in herd

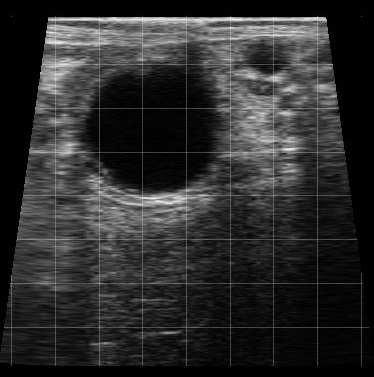

If the presence of actively circulating BVD virus is suspected in a herd we can investigate further by looking for either the virus itself (‘antigen’) or antibodies against the virus. The lab tests can be run on individual or pooled samples of blood, milk or tissue. By blood sampling groups of young stock between 9 and 18 months old we can determine if animals are being exposed before they enter the milking herd. This is the basis of herd eradication schemes including the Gwaredu BVD scheme in Wales. Alternatively all young stock can be ‘Tag and Tested’ using ear tags which take a sample to see if virus is present within the calf’s ear tissue. Your herd should have a bespoke action plan to eradicate BVD which will be drawn up with your herd’s specific circumstances in mind. Your vet will be able to create a workable plan for your farm.

Eradicating the disease from a herd requires consideration of three main areas:

1. Biosecurity – measures to prevent the introduction of PI animals

2. Identification and removal of PIs – these animals are highly infective and exert an enormous infection pressure within the herd.

3. Vaccination – ensure that cows are not infected in the first third of pregnancy, and limiting the risk chance of transfer to the foetus.

Fluke

Fluke, caused by parasite Fasciola hepatica, affects both sheep and cattle. The cost of the disease nationally is huge, through reduced productivity and damage to livers which are then not fit to enter the food chain.

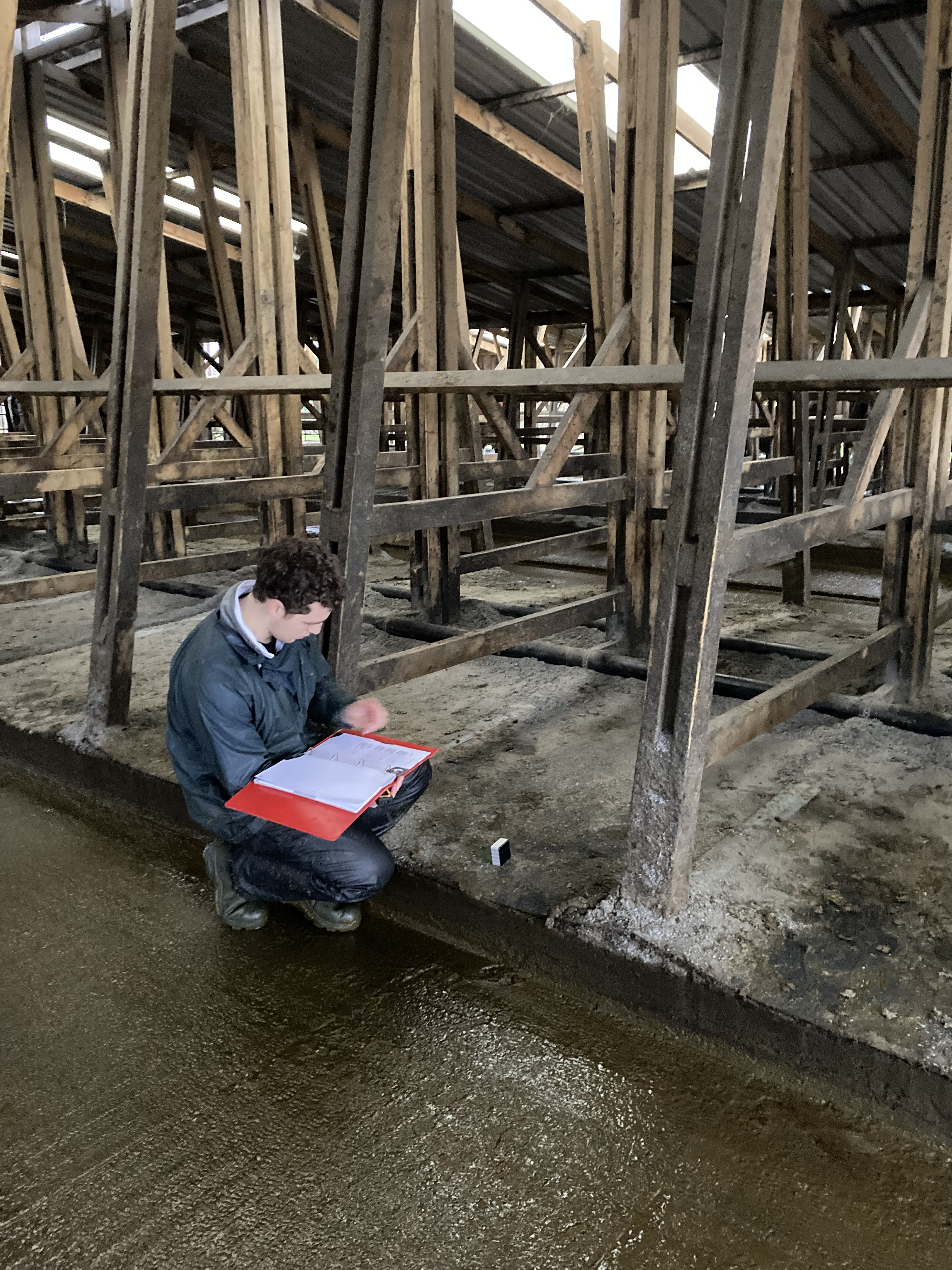

The life cycle of the fluke parasite relies on the mud snail (Galba truncatula) acting as an intermediate host. The snail thrives in muddy and slightly acidic areas, such as ground with poor drainage, banks of ditches or streams but can also form temporary habitats around muddy troughs and gateways. As a result the incidence of liver fluke is much higher in areas of the country with more rainfall, and in years with wetter summers.

The immature fluke stages are able to ‘overwinter’ in the snail, so even if cattle are treated there remains a permanent source of infection in the snail. As a result, an important part of fluke control is preventing cattle from accessing areas of heavy snail infestation.

The snails can reproduce very rapidly: 100,000 offspring in 3-4 months. Combined with rapid multiplication of the fluke parasite within the snails, wet conditions allow huge numbers of the infectious form of the parasite (‘metacercariae’) to be shed onto pasture. In infected areas each blade of grass may be home to up to 20 metacercariae, of which only 200 are required to cause disease – that’s only 10 blades of grass which need to be eaten!

These immature forms of fluke are ingested with grass and develop into adult fluke inside the animal. The adults go on to produce the eggs which are passed in the faeces before they develop on the grass to infect the snail.

Once in the cow (or sheep), all stages of the life cycle can cause disease. The immature stages tunnel through the liver causing severe damage. Once they reach the bile duct and mature into adults, they feed on the animals’ blood (around 0.5ml/fluke/day) and lead to the chronic form of the disease.

Clinical signs include

- Sudden death (acute form)

- Loss of condition

- Reduced milk quality and yield

- Reduced weight gain

- Fertility problems

- Chronic anaemia

- Condemned livers at slaughter

- Increased susceptibility to Salmonella and liver disease

Diagnosing fluke infection is based on a combination of clinical signs and testing, with consideration of the weather conditions and farm history. Faecal fluke egg counts can further support a diagnosis; however they often fail to detect fluke infections before the adult (egg-shedding) fluke has been reached. Adults are not present until 8-12 weeks after infection, and even then only intermittently shed eggs.

Antibody tests are also available – these can be performed on blood or milk samples and can be more sensitive as they can detect infection before adult fluke have developed and do not rely sporadic shedding of eggs.

As part of the Infectious Disease Check programme we are monitoring bulk milk antibody levels. This allows us to gauge the herd’s level of exposure and roughly evaluate the success of the fluke control plans we have in place. In some circumstances we have found that fluke antibody levels are high enough to warrant further investigation, or to make changes to fluke control plans.

Prevention of fluke is always preferable to treating the disease. The level of infection can be controlled to a certain extent by reducing the amount of contact between the cattle and snail populations. This can be achieved by:

- Increasing drainage of the fields

- Fencing off access to still or slow flowing water

- Controlling the snail population

- Removing cattle from fields likely to flood

- Avoid autumn grazing of damp pasture

- Use lime to alter pH of soil to slightly alkali

The next round of Infectious Disease Check sampling is now underway! Those of you not milk recording with CIS should look out for a sample pot in the post. If you don’t receive one by the end of the month please let us know.

Leave A Comment