The TB tests we use in cattle are extremely poorly understood and/or explained and are often bemoaned as being responsible for the problem of TB persisting and spreading through our countryside. We thought a review of the tests would be a useful thing for our clients. As many of you know Den spends much of his time boring people about TB so we thought we’d let him loose on the subject of TB tests.

TB was one of the most prevalent human diseases before milk pasteurisation. It has been eradicated and indeed eliminated from most of the developed world using a combination of testing, culling of carrier animals and restricting movements of cattle. As a country we have an international obligation to have a control scheme in place for TB which allows us to legally sell produce and to move animals around the country and importantly internationally. Testing is one part of this control program and there are two main tests in use by our government – the Single Intradermal Comparative Cervical Tuberculin (SICCT) test, which we call the ‘skin test’, and the Interferon-gamma blood test.

The Skin Test

The skin test (SICCT) involves injecting the cow with 2 different versions of Tuberculin and then seeing whether this causes a reaction (lump) 3 days later. Tuberculin is a protein made by M. bovis bacteria (which is the bottom injection) and a protein from a related bacteria (avian tuberculin – the top injection). In some countries they only use bovine tuberculin and kill anything that makes a lump but, by using the avian injection we can stop ourselves killing animals that are not truly infected with TB and are just cross reactions to other Mycobacteria including Johne’s. Farmers (and indeed some vets) commonly get the failings of this test completely the wrong way around. This test’s weakness is its sensitivity. The sensitivity of the skin test under standard interpretation is around 80%.

This means that it will miss around 1 in 5 infected cows. However because we use the skin test across both farms and indeed areas repeatedly, this sensitivity issue is not poor enough for us to miss infected farms or areas in most situations. It is also why when we have infected farms or areas we do a lot of repeat testing before we get more confident that the herd/area is clear of infection. However, as a test for a handful of animals (such as premovement tests) it is capable of being quite limited in finding infection.

So why on earth do we use it? The reason is it has an amazingly high specificity, which is 99.98%. This means that if you have a positive result to the test, there is only a 1 in 5000 chance that that cow is not infected (false positive). This will surprise many of you because many of the cows (around 60% annually) we send off as reactors do not show visible disease (lesions) or bacteria in them (culture) and this means the government tell you they haven’t found disease at that moment in time, which is quite misleading unfortunately. Take home message – if she reacts, she is definitely infected, no matter what they fail to find in the slaughterhouse. When we find infection we can make the skin test more sensitive by doing what is known as ‘severe interpretation’. This means we call the animal a reactor a bit keener, based on her producing just a small lump. The specificity drops a little bit but is still pretty high. The upside is the sensitivity improves a lot so we miss less infected cows under severe interpretation, which hastens the discovery of infection in the herd.

A final failing of the skin test is ‘anergic cows’. These are heavily lesioned cows that are so badly infected the immune system sort of gives up and fails to make a reaction. These cows are often discovered at slaughter as they are full of lesions. Thankfully they are not that common in areas that test regularly, but everyone loves talking about them so they feel more common than they are.

The blood test or ‘Gamma test’

These days we have other tests for TB at our disposal, and a commonly used test now is the Gamma test. This is a blood test and returns a result in a few days. The gamma test is much more sensitive than the skin test at around 90%, but the specificity is lower at around 97%. Sounds a pretty good test? Well be careful what you wish for, because specificity is more important than sensitivity where there is very little disease. In other words if you gamma tested your herd of 200 cows, you might expect 3% to be false positive or 6 cows. This is why gamma is restricted to high risk cattle, such as inconclusives, or occasionally in-contact animals where there’s a high rate of reactors in a group and further infection is considered likely. You are allowed to apply for your own animals to be gamma tested privately as long as the government agree that it makes sense. Take home message – the gamma test finds more infection but also kills a few innocent cows doing it.

The Enferplex test

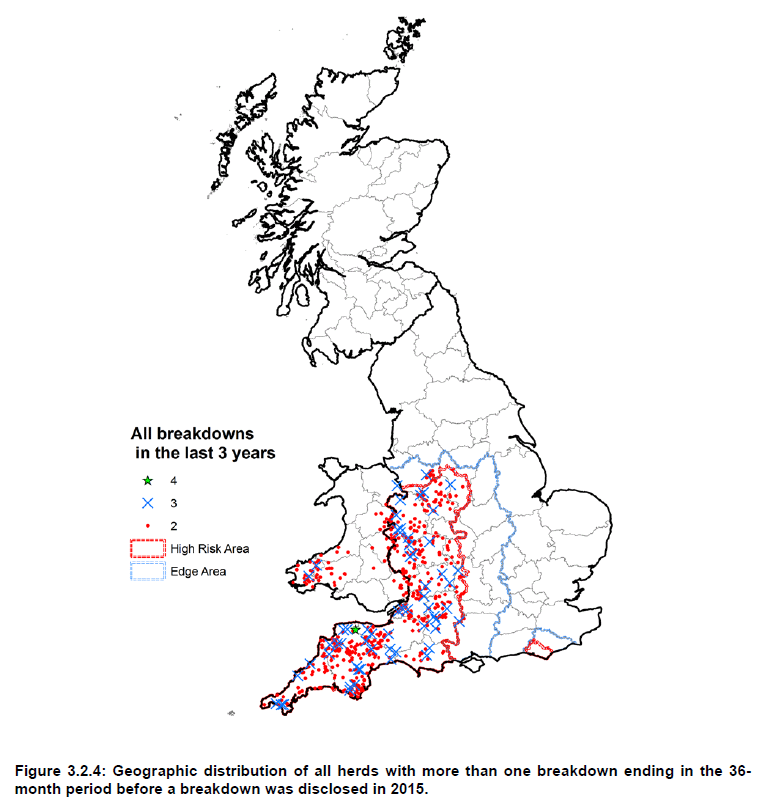

There is a new blood test being used now called the Enferplex or Phage test. This test looks for a number of different antigens so the specificity and sensitivity varies a bit depending on how many of the antigens you find. In a nutshell it is similar in some ways to the gamma test in terms of sensitivity and specificity, although it’s specificity can be adjusted to be quite high, but causes compromises in sensitivity at these higher levels. It is finding animals that the skin test is missing so may be useful in the future. It also doesn’t test positive in vaccinated cows, so should vaccination ever be part of our control program it could prove useful. It also is very useful as a test in camelids, which is great as they are particularly prone to TB infection and have in some cases infected their owners. It is not being used widely at the moment but we watch with interest as we increase our understanding of how best to use it. Although often heavily criticised, reassuringly our testing regime works particularly well in all the areas of the UK where there is limited background wildlife infection. Despite us introducing to and discovering infection in the Low Risk Area (LRA) and Scotland every year via cattle movements, the 2015 annual government report showed no farms in those areas having repeat breakdowns (see map) because once discovered the restrictions and testing regime applied relatively quickly bring the outbreak to an end. This lets us know that we do not need any new tests or approaches to get this disease under control, we simply need to stop moving it around so much in cattle, make sure we carry on with our cattle testing and also reduce (under license) the infection pressure from our wildlife. Depending on feedback we can do regular updates about TB issues – let us know whether you would value that.

Leave A Comment